|

|

|

2016-2017 AP Euro class had a 94% Pass

Rate!!!!!!!!!!

Twelfth Grade AP European History

Syllabus

AP

European History HOMEWORK FORMATT

Map

Quiz; AP European History

AP History Skills Basics:

AP History Skills

in detail:

Handouts on various content

topics

Teacher: Mr. Kay

East Lake High School

Purpose:

The purpose of this course is to teach you

European History from a European point of view in order for you to

pass the AP European History exam. If you do well enough on

the exam you will earn college credit and obtain money for your

school. The course will therefore be taught with the

expectation that you will do all the necessary work needed to pass

this test.

Overview:

This course will cover the major topics in

European history from the Renaissance to the present. It will

focus on Europe and how Europeans reacted to the rest of the world.

It should be remembered that this is NOT a world history course and

that the student should not assume that because we are studying

Europe that Europe is more important than anywhere else.

Today, Europeans are some of the most powerful and influential

people in our world and their history is very important to an

understanding of world history. However, at different periods

of time, different areas of the world have been powerful. For

example, during the Ming dynasty in China or during the rule of the

Pharaohs in Egypt, Europe was an inconsequential backwards place.

All areas of the world have had their time of glory and all areas of

the world have contributed to our history (for example, surgery was

invented in Egypt as well as other areas). Some of the major

topics we will cover are the Renaissance, the French Revolution, the

Scientific Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, World Wars I and

II and the Cold War.

Supplies:

It is expected that all students will have

their own supplies which includes a three ring binder that we will

use to keep both a notebook and a writing folder. Please note

you can choose to have paper in your three ring binder to serve as

your notebook but you must have a folder that can be turned in

separately for the writing folder

Grades:

Grades are to be determined based on the

following formula: Tests=60%, Quizzes=30%, Homework= 10%.

The low percentage on homework is because you will use it during

quizzes. There will be a quiz on every chapter at the

beginning of class BEFORE the teacher has reviewed it and if you do

not do your homework then your quiz grade will be substantially

lower. Quiz formats will include 5-10 AP multiple choice

questions and one essay question that you will write a thesis

statement for and provide facts as support. Tests will be AP

style tests with multiple choice, DBQ and essay.

You will also get a double test grade for the book you will choose

to read by the end of semester 1. (More on this later.)

The Curve

Historically, grades in AP classes tend to be

remarkably low. This is because of the difficulty of the work

and the variety of skill levels in a class. Since as honor

students bound for college, we do not want to see anyone’s GPA

destroyed there will be points earned in the replaying of history in

class. It should be clear that since this is extra potential

points that there are no guarantees. You can still find

yourself with a low grade if you do not do the work. In

addition, since these points are added after the curve has been

determined, there is no guarantee they will be enough to change the

grade. This grade change will never be more than 4 percentage

points and usually much less. However the added incentive will

make our reenactments more realistic.

Attendance:

It is extremely important that you be here for

every class. However if you are forced to be absent then any

assignment (including a quiz or a test) that was due on the day you

were absent is due on the day you return. Work will not be

accepted unless the absence is excused and absences may be confirmed

by parental contact. You are also responsible for all work

done during your absence. It is highly recommended that you

obtain the phone number of several classmates so that you may obtain

any make-up work.

**************************************************************

Please note that your first homework

assignment is to send me an email stating that you understand the

syllabus!

***************************************************************

**Please note in order to respect privacy

and the rights of minors, these email addresses will not be given

out.

AP European History

HOMEWORK FORMATT

HOMEWORK CHART

Name___________________

Chapter Title and Number________________________________________________________________________

Time Frame:___________________________

Main Ideas/Events:

Summation/Results

PAGE2 and beyond

***********************************************************

pp.________

Dates

Section

Title:

Meaning

SPECIFICS!!!

Maps/Charts

Map

Quiz; AP European History

For numbers 1-33

match the word to the key on the map and fill out your scantron.

-

Atlantic ocean

-

Mediterranean Sea

-

Black Sea

-

Agean Sea

-

Caspian Sea

-

North Sea

-

Adriatic Sea

-

Alps

-

Pyrennees

-

Urals

-

Compass North

-

South

-

East

-

West

-

Russia

-

England

-

France

-

Germany

-

Italy

-

Poland

-

Czech Republic

-

Norway

-

Sweden

-

Denmark

-

Greece

-

Turkey

-

Crimea

-

Ukraine

-

Straits of Gibraltar

-

Ireland

-

Finland

-

Iceland

-

Normandy

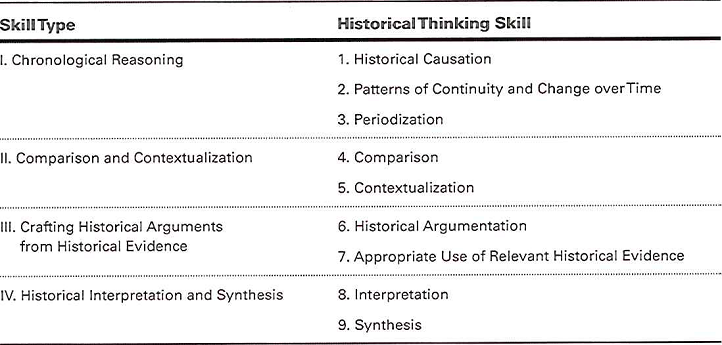

AP History Skills Basics:

The following skills are necessary for success on the

AP Exam. These are used at all

levels of questions and in all the essays and short answers.

All quizzes and tests will reflect these skills and all

students should be proficient at all levels to succeed.

For more detail go to:

http://www.sargenotes.com/historical-thinking-skills---old.html

AP History Skills:

1. Historical Causation

Historical thinking involves the ability to identify,

analyze, and evaluate the relationships among multiple historical causes and

effects, distinguishing between those that are long-term and proximate, and

among coincidence, causation, and correlation.

Proficient students should be able to:

Compare causes and/or effects, including between

short-term and long-term effects.

Analyze and evaluate the interaction of multiple causes

and/or effects.

Assess historical contingency by distinguishing among

coincidence, causation, and correlation, as well as critique existing

interpretations of cause and effect.

2. Patterns of Continuity

and Change over Time

Historical thinking involves the ability to recognize,

analyze, and evaluate the dynamics of historical continuity and change over

periods of time of varying length, as well as the ability to relate these

patterns to larger historical processes or themes.

Proficient students should be able to:

Analyze and evaluate historical patterns of continuity

and change over time.

Connect patterns of continuity and change over time to

larger historical processes or themes.

3. Periodization

Historical thinking involves the ability to describe,

analyze, evaluate, and construct models that historians use to divide

history into discrete periods. To accomplish this periodization, historians

identify turning points, and they recognize that the choice of specific

dates accords a higher value to one narrative, region, or group than to

another narrative, region, or group. How one defines historical periods

depends on what one considers most significant in

society — economic, social, religious, or cultural life — so historical

thinking involves being aware of how the circumstances and contexts of a

historian’s work might shape his or her choices about periodization.

Proficient students should be able to:

Explain ways that historical events and processes can

be organized within blocks of time.

Analyze and evaluate competing models of periodization

of European history.

4. Comparison

Historical thinking involves the ability to describe,

compare, and evaluate multiple historical developments within one society,

one or more developments across or between different societies, and in

various chronological and geographical contexts. It also involves the

ability to identify, compare, and evaluate multiple perspectives on a given

historical experience.

Proficient students should be able to:

Compare related historical developments and processes

across place, time, and/or different societies, or within one society.

Explain and evaluate multiple and differing

perspectives on a given historical phenomenon.

5. Contextualization

Historical thinking involves the ability to connect

historical events and processes to specific circumstances of time and place

and to broader regional, national, or global processes.

Proficient students should be able to:

Explain and evaluate ways in which specific historical

phenomena, events, or processes connect to broader regional, national, or

global processes occurring at the same time.

Explain and evaluate ways in which a phenomenon, event,

or process connects to other similar historical phenomena across time and

place.

6. Historical

Argumentation

Historical thinking involves the ability to define and

frame a question about the past and to address that question through the

construction of an argument. A plausible and persuasive argument requires a

clear, comprehensive, and analytical thesis, supported by relevant

historical evidence — not simply evidence that supports a preferred or

preconceived position. Additionally, argumentation involves the capacity to

describe, analyze, and evaluate the arguments of others in light of

available evidence.

Proficient students should be able to:

Analyze commonly accepted historical arguments and

explain how an argument has been constructed from historical evidence.

Construct convincing interpretations through analysis

of disparate, relevant historical evidence.

Evaluate and synthesize conflicting historical evidence

to construct persuasive historical arguments.

7. Appropriate Use of

Relevant Historical Evidence

Historical thinking involves the ability to describe

and evaluate evidence about the past from diverse sources (including written

documents, works of art, archaeological artifacts, oral traditions, and

other primary sources), and requires paying attention to the content,

authorship, purpose, format, and audience of such sources. It involves the

capacity to extract useful information, make supportable inferences, and

draw appropriate conclusions from historical evidence, while also noting the

context in which the evidence was produced and used, recognizing its

limitations and assessing the points of view it reflects.

Proficient students should be able to:

Analyze features of historical evidence such as

audience, purpose, point of view, format, argument, limitations, and context

germane to the evidence considered.

Based on analysis and evaluation of historical

evidence, make supportable inferences and draw appropriate conclusions.

8. Interpretation

Historical thinking involves the ability to describe,

analyze, evaluate, and construct diverse interpretations of the past, and to

be aware of how particular circumstances and contexts in which individual

historians work and write also shape their interpretation of past events.

Historical interpretation requires analyzing evidence, reasoning, contexts,

and points of view found in both primary and secondary sources.

Proficient students should be able to:

Analyze diverse historical interpretations.

Evaluate how historians' perspectives influence their

interpretations and how models of historical interpretation change over

time.

9. Synthesis

Historical thinking involves the ability to develop

meaningful and persuasive new understandings of the past by applying all of

the other historical thinking skills, by drawing appropriately on ideas and

methods from different fields of inquiry or disciplines, and by creatively

fusing disparate, relevant, and sometimes contradictory evidence from

primary sources and secondary works. Additionally, synthesis may involve

applying insights about the past to other historical contexts or

circumstances, including the present.

Proficient students should be able to:

Combine disparate, sometimes contradictory evidence

from primary sources and secondary works in order to create a persuasive

understanding of the past.

Apply insights about the past to other historical

contexts or circumstances, including the present.

Send comments and questions to

Professor Gerhard Rempel, Western New England College.

Louis XIV: THE SUN

KING

“L’Etat C’est Moi!”

“Un Roi, Une Loi, Une Foi”

1694-1778

(FRANCOIS MARIE AROUET)

For nearly 50 years Voltaire preached freedom of thought and denounced

cruelty and oppression in all its forms. Voltaire was bourgeois, not a

democrat. He believed in reasonable dissent. He believed in natural religion

and praised French artistic and cultural achievement during the Age of Louis

XIV. Politically he advocated the concept of Enlightened Despotism. Above

all others Voltaire stood as the champion of reason and tolerance. As a

young man he was known in Paris for his plays and his wit and conversation.

He once offended the aristocrat Chevalier de Rohan, who, too proud to fight

a duel with a commoner ordered his servants to give Voltaire a street

beating. He was then ordered to the Bastille. By agreeing to leave France

Voltaire was granted his freedom. He immediately left for England.

While in England he found that he could say what he pleased and was not

beaten for it. He quickly fell in love with a country where literary men and

scientists were highly respected. In 1727 he attended the funeral of Isaac

Newton and later wrote that he was overwhelmed to see "a professor of

mathematics buried like a king."

During his tenure in England he wrote Letters on the English (1733).

"The English, as a free people choose their own road to heaven. Here the

nobles are great without insolence, and the people share in the government

without disorder."

In 1734 he returned to France and his Letters on the English was

published in his own country. Unfortunately this work angered both the

government and the church and it was ordered to be burned in public as being

"scandalous, contrary to religion, to morals and to respect for authority."

Such a sentence only served to spur others to sample the forbidden fruit.

Once again to avoid the Bastille, Voltaire went into hiding, this time with

friends in Lorraine.

These early experiences set the stage for the remainder of Voltaire's life.

Voltaire developed an extreme hatred for oppression and for the rest of his

life he waged a personal war on intolerance and persecution for opinion's

sake. He found that only in foreign countries (Switzerland, Holland, England

and Prussia) could a man say what he thought about religion and politics.

Voltaire lived for the limelight and thus wrote plays, which thousands saw

at the theaters. He tried his hand at a variety of literary endeavors:

entertaining tales (Candide), scientific treatises (The Philosophy

of Newton), poetry (On the Lisbon Earthquake), and letters,

always letters to nearly everyone of importance and acquaintance. But in all

of these he carried on his war against intolerance.

Additionally he was an historian and wrote a history of the world from

early times to his own (An Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations)

which was published in 1756. This was perhaps his most influential work.

He used history to demonstrate his theme that persecution and intolerance

were both unjust and useless. This was done by showing that the greatest

advancement in knowledge occurred when there was the greatest freedom of

thought. His writings demonstrated that this was best displayed during the

classical age of Greece and Rome, during the Renaissance and in the 17th and

18th centuries. He contended, that in the Middle Ages, when the church held

sway that thought was restricted and there "existed great ignorance and

wretchedness--these were the Dark Ages." Voltaire exaggerated both the

ancient world's qualities of good, and the Middle Ages' qualities of

"horror." But this only made people read his work all the more.

Voltaire was not an atheist, but he was against any and all religions that

were opposed to freedom of thought. Thus he became a bitter enemy of the

Catholic Church as it existed in France. As he aged he spewed a great and

greater venom against the church. Beginning in his early 60's he began to

sign his letters to his friends with the phrase "Ecraser l'infame!"

(Crush the infamous thing!) Voltaire clearly meant the spirit of persecution

but his enemies proclaimed that he was ridiculing the Catholic Church.

In 1762 the aged Voltaire began to champion the causes of strangers who

were persecuted unjustly. Such as man was Jean Calas a Huguenot shopkeeper

in Toulouse who was accused and convicted of murdering one of his sons on

the pretext that he wanted to become a Catholic. With anti Huguenots fervor

Jean Calas was tortured and then broken on the wheel and his other children

were forced to become members of monastic orders. There was never any real

evidence of murder presented. Voltaire saw this as clearly a case of

religious persecution and he worked to have the case overturned. Three years

later the case was retried in Paris and the verdict overturned. This case

became famous throughout Europe and earned Voltaire a great deal of honor as

the champion of human rights.

In the year of his death, 1778, Voltaire returned to Paris. He was met at

the frontier by a customs official who question him as the there being

contraband in his carriage. Voltaire's reply was "Nothing but myself."

Why was Voltaire so admired throughout Europe? Perhaps it is as one

observer replied when asked who was that man. She replied "That is the

savior of Calas." Perhaps it is because he live for a long time and wrote a

great deal. More than likely is stemmed from the fact that his works were

read because they were so well written. His works filled more than 90

volumes. He died on the eve of the French Revolution and helped to create a

atmosphere in which most people no longer believed in the divine right of

the state or the church.

The

Wit and Wisdom of Voltaire:

In general the art of government consists in taking as much money as

possible from one class of citizens to give it to the other.

Marriage is the only adventure open to the cowardly

I have never made but one prayer to God, a very short one: "Oh Lord, make my

enemies ridiculous" And God granted it.

Self Love never dies

The gloomy Englishman, even in his loves, always wants to reason. We are

more reasonable in France.

Men use thought only to justify their wrongdoings, and employ speech only to

conceal their thoughts.

It is said that God is always on the sides of the biggest battalions

All the reasoning of men is not worth one sentiment of woman.

To stop criticism they say one must die.

VOLTAIRE ON

SUPERSTITION

"Almost everything that goes beyond the adoration of a Supreme Being and

submission of the heart to his orders is superstition. One of the most

dangerous is to believe that certain ceremonies entail the forgivness of

crimes. Do you believe that God will forget a murder you have committed if

you bathe in a certain river, sacrifice a black sheep, or if someone says

certain words over you?...Do better miserable humans; have neither murders

nor sacrifices of black sheep...

|

|

Lecture 7

The Medieval Synthesis and the Secularization of

Human Knowledge: The Scientific Revolution, 1642-1730 (2)

|

|

If I

have seen further it is because I have stood on the shoulders of

giants.

---Isaac Newton

The end result

of my study of Newton has served to convince me that with him

there is no measure. He has become for me wholly other, one of

the tiny handful of supreme geniuses who have shaped the

categories of the human intellect, a man not finally reducible

to the criteria by which we comprehend our fellow beings.

---Richard Westfall, Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac

Newton

We can't imagine that the Scientific

Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries took place in a

vacuum. That is, we can't assume that modern science simply came

to be in a momentary flash of brilliance, nor that Copernicus or

Kepler or Galileo just woke up one morning and pronounced their

discoveries to a world which became somehow instantaneously

different (see

Lecture 6). Past historians have

looked at the history of modern science from precisely this

point of view. Like the Renaissance, the Scientific Revolution

has been interpreted as explosive, a surge forward, a watershed.

On this score, John Herman Randall once remarked that:

One gathers,

indeed, from our standard histories of the sciences, written

mostly in the last generation, that the world lay steeped in the

darkness and night of superstition, till one day Copernicus

bravely cast aside the errors of his fellows, looked at the

heavens and observed nature, the first man since the Greeks to

do so, and discovered . . . the truth about the solar system.

The next day, so to speak, Galileo climbed the leaning Tower of

Pisa, dropped down his weights, and as they thudded to the

ground, Aristotle was crushed to earth and the laws of falling

bodies sprang into being.

[The Career of Philosophy, vol 1, 1962]

The scientists of the seventeenth century

-- those mathematicians, astronomers, and philosophers -- had

the enormous weight of centuries of thought resting on their

shoulders. Even Isaac Newton was aware of the debt he owed to

the past. Although this tradition was based largely on the work

of

Aristotle,

St. Augustine,

Aquinas and

Dante, the scientific revolutionaries

sought to break free from these traditional beliefs. They had to

forge a new identity. The scientific revolutionaries needed to

transcend

Plato, Aristotle,

Galen,

Ptolemy or Aquinas -- this was their

conscious decision. They not only criticized but replaced the

medieval world view with their own. And this quest for identity

would culminate in a world view that was scientific,

mathematical, methodological and mechanical.

However, this revolution was accomplished

by utilizing the medieval roots of science which, in turn, meant

the science of the classical age of Greece and Rome as well as

the refinements to that science made by Islamic scholars. They

used what they found at hand to create a new outlook on the

cosmos, the natural world and ultimately, the world of man. The

antecedents to this revolution in thought are found in the 11th

and 12th centuries when most of the ideas of the ancient Greek

philosophers were wed together into a new body of beliefs. These

beliefs were living and vital. We encounter them in the 12th

century Renaissance (see

Lecture 2). We find them at the school

of Chartres in the mid-12th century, or at the medical school at

Salerno near Naples in 1060. At Toledo in Spain, 92 Arabic works

had been translated along with Ptolemy in 1175. By the 12th

century, Arabic science and mathematics had found its way to

Oxford in England and to Padua in Italy. From the early 12th

century, then, there existed in Europe a continuous tradition of

scientific endeavor. And although this science was temporarily

overshadowed by the intellectual bulk of Aristotle in the

mid-13th century, this tradition was living in the 15th and 16th

centuries and well into the 17th.

This was the background and education of the scientific

revolutionaries. We must see their discoveries as shaped and

formed by this core of accepted ideas and not just spinning out

of empty space. The revolution in science did not occur quickly.

It developed over time. Although the medieval Church earned

absolute power, authority and obedience, science and scientific

thinking did flourish during the five centuries preceding that

watershed we call the Scientific Revolution.

By

the 17th century, science, scientific thinking and the

experimental method had become the territory of more men, and by

the mid-18th century, increasing numbers of women would be

included as well. For instance, In 1649 René Descartes yielded,

after much hesitation, to the requests of Queen Christina of

Sweden that he join the distinguished circle she was assembling

in Stockholm and personally instruct her in philosophy.

The New Science spread rapidly through education in universities

such as Oxford, Cambridge, Bologna, Padua and Paris. Science was

also diffused to a large audience through books. Each time a

Galileo, Descartes, or Newton published their findings, a wave

of replies followed. And each of these replies was followed by

other replies so that what quickly resulted was an ever growing

body of scientific literature. And, of course, there was at the

same time, an increasing number of men and women who were eager

for such knowledge.

By the end of the 17th century, new

societies and academies devoted to science were founded. There

were many who agreed with

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) that

scientific work ought to be a collective enterprise, pursued

cooperatively by all its practitioners. Information should be

exchanged so that scientists could concentrate on different

parts of a project rather than waste time in duplicate research.

Although it was not the first such academy, the Royal Society in

England was perhaps the first permanent organization dedicated

to scientific activity. The

Royal Society was founded at Oxford

during the

English Civil War when revolutionaries

captured the city and replaced many teachers at the university.

A few of these revolutionaries formed the Invisible College, a

group that met to exchange information and ideas. What was most

important was the organization itself, not its results: the

group only included one scientist,

Robert Boyle (1627-1691). In 1660,

twelve members, including Boyle and

Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723),

formed an official organization, the Royal Society of London for

Improving Natural Knowledge. In 1662, the Society was granted

its charter by Charles II.

The purpose of the Royal Society was Baconian to the core. Its

aims was to gather all knowledge about nature, particularly that

knowledge which might be useful for the public good. Soon it

became clear, however, that the Society's principal function was

to serve as a clearing center for research. The Society

maintained correspondence and encouraged foreign scholars to

submit their discoveries to the Society. In 1665 the Society

launched its Philosophical Transactions, the first

professional scientific journal. The English example was

followed on the continent as well: in 1666 Louis XIV accepted

the founding of the French Royal Academy of Sciences and by

1700, similar organizations were established in Naples and

Berlin.

The New Science was also diffused by public demonstrations. This

was especially the case in public anatomy lessons. Scientist and

layman alike were invited to witness the dissection of human

cadavers. The body of a criminal would be brought to the lecture

hall and the surgeon would dissect the body, announcing and

displaying organs as they were removed from the body.

Throughout major European cities there were wealthy men who,

with lots of free time on their hands, would dabble in science.

These were the virtuosi -- the amateur scientists.

These men oftentimes made original contributions to scientific

endeavor. They also supplied organizations like the Royal

Society with needed funds.

By

1700, science had become an issue of public discourse. The

bottom line, I suppose, was that science worked! It was

wonderful, miraculous and spectacular. For the 17th century

scientist -- a Galileo, a Newton or the virtuosi --

science produced the Baconian vision that anything was indeed

possible. Science itself gave an immense boost to the general

European belief in human progress, a belief perhaps initiated by

the general awakening of European thought in the 12th century.

It was the achievement of men like

Copernicus and

Galileo sift through centuries of

scientific knowledge and to create a new world view. This was a

world view based as much on previous science and knowledge as it

was on new developments derived from the scientific method.

The greatest scientific achievement of the 17th century was

clearly the mathematical system of the universe produced by

ISAAC NEWTON (1642-1727). It was

Newton who went far beyond Galileo by taking observations of the

heavens and turning them into measured and irrefutable fact.

Thanks to Newton, the western intellectual tradition would now

include a concrete and scientific explanation of the motion of

the heavens. Because of his greatness, the 17th century could

almost be called the Age of Newton.

Newton was in his own lifetime not regarded as a genius by his

contemporaries. His fellow scientists respected him and admired

him but they also disliked him. The reason is clear -- Newton

was not a happy man. He was dour, sour and made absolutely no

attempt to befriend anyone. Whenever someone happened to get too

close to him, he retired to his study. His thoroughgoing

Puritanism meant that he constantly subjected himself to

self-examination.

Isaac Newton was born premature on Christmas Day, 1642, the year

of Galileo's death. His family belonged to the gentry. He was

educated at Cambridge and was also a member and president of the

Royal Society. Although the Society was responsible for the

publication of his major writings, his relationships with its

members was strained. In the 25-30 years that Newton was a

member he attended its meetings only a handful of times. In

terms of religion he accepted the Church of England only

partially. Over time, he came to see the Bible more as an

allegory than as undisputed fact.

He was an unlikable man -- a solitary

genius. He worked in short bursts of energy and was always

hesitant to publish his findings. He had to be coaxed and

encouraged to make those simplifications necessary to

communicate a considerable body of thought. He quarreled

violently with those men (e.g.,

Hooke,

Leibniz and Flamstead) who questioned

his priority and superiority in fields he dominated.

Modern biographers have pretty much agreed that Newton -- our

"sober, silent, thinking lad" -- suffered a troubled childhood.

His father died in early October 1642, a month before Isaac was

born. For the first three years of his life he was sent out to a

wet nurse and then lived with his grandmother. During this time

his mother remarried, an act that did much to alienate Newton

from his mother. As a child, Newton was never shown much love or

affection. This may explain why he was always so isolated,

detached and unemotional.

Between 1660 and 1690, Newton devoted

himself to an

academic life at Cambridge. As the

Lucasian Chair of Mathematics he was expected to lecture on a

weekly basis, lectures which he frequently delivered to empty

classrooms. He embraced a number of academic interests but the

ones which interested him most were alchemy, theology, optics

and mathematics. No field of study took precedence over another

and he so he devoted as much of his energy and intellect to

alchemy as he did to theology and mathematics.

Like most scholars of the period, Newton had an amanuensis,

a young student who served him as an assistant who provided

Newton with meals as well as transcriptions of his lecture

notes. Newton was an absent-minded man. Stories of Newton's

behavior are, of course, well known. Newton was a deliberate

thinker, always hesitant to publish, always hesitant to move too

quickly. A call to dinner might have taken Newton an hour to act

upon. If, on his way to sup, his fancy was struck by some book

lying on the table, the meal would simply have to wait. He ate

poorly, slept irregularly and for the most part found the

outside world a terrible irritant from which he needed to

escape. [Readers interested in "Newton the Man," would do well

to consult Westfall's biography (mentioned above) as well as

Frank Manuel's excellent psycho-biography, A Portrait of

Isaac Newton (1968).]

In

1687, Newton finished his greatest work,

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy),

the last "great" work in the western intellectual tradition to

be published in Latin. It was this work, commonly called the

Principia, which secured Newton's place as one of the

greatest thinkers in the intellectual history of Europe. The

Principia is a dense work, but not totally

incomprehensible. He wanted to explain why the planets were held

in their orbits -- he wanted to know why an apple fell to the

earth. His answer was, of course, gravity. Newton not only

described the laws which explained gravity, he also invented the

calculus to explain the laws of gravity. In

1687, Newton finished his greatest work,

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy),

the last "great" work in the western intellectual tradition to

be published in Latin. It was this work, commonly called the

Principia, which secured Newton's place as one of the

greatest thinkers in the intellectual history of Europe. The

Principia is a dense work, but not totally

incomprehensible. He wanted to explain why the planets were held

in their orbits -- he wanted to know why an apple fell to the

earth. His answer was, of course, gravity. Newton not only

described the laws which explained gravity, he also invented the

calculus to explain the laws of gravity.

Even for those people who could not

understand Newtonian physics or mathematics, Newton had an

amazing impact, since he had offered irrefutable proof --

mathematical proof -- that Nature had order and meaning, an

order and meaning that was not based on faith but on human

Reason. With Newton, we find the important combination of two

important concepts -- Nature and Reason. His scientific

discoveries and his spirit dominated the thought of the 18th

century -- a century dubbed the Age of Enlightenment (see

Lecture 9).

In 1727, the year of Newton's death, the

English poet

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) composed an

epitaph for Newton's grave at Westminster Abbey. His epitaph was

short and precise and illustrates the importance of this

solitary genius. Pope wrote:

Nature and

Nature's laws lay hid in night:

God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.

How can it be that a poet who was then working on a new

translation of Homer, should come to write Newton's epitaph? Was

Pope also a mathematician? Hardly. The point is that Pope knew

that Newton had discovered something which would in the 18th

century become universally applicable to the new science of man.

If man, using his Reason, could deduce the laws of Nature, then

it seemed only a short step to apply those laws to man and

society. Is it any accident that the modern social sciences were

founded in the 18th century and in the wake of Newton's

achievement?

The Scientific Revolution gave the western world the impression

that the human mind was progressing toward some ultimate end.

Thanks to the culminating work of Newton, the western

intellectual tradition now included a firm believe in the idea

of human progress, that is, that man's history was one of the

progressive unfolding of man's capacity for perfectibility. From

this point on, man the believer was now joined by man the

knower. It was man's destiny to both know the world, and create

that world.

But, the Scientific Revolution also showed

man to be merely a small part of a larger divine plan. Man no

longer found himself at the center of the universe -- he was now

simply a small part of a much greater whole. The French thinker

BLAISE PASCAL (1623-1662), gave

perhaps the greatest expression to the uncertainties generated

by the Scientific Revolution when, in his

Pensées, he wrote:

For,

after all, what is man in nature? A nothing in comparison with

the infinite, an absolute in comparison with nothing, a central

point between nothing and all. Infinitely far from understanding

these extremes, the end of things and their beginning are

hopelessly hidden from him in an impenetrable secret. He is

equally incapable of seeing the nothingness from which he came,

and the infinite in which he is engulfed. What else then will he

perceive but some appearance of the middle of things, in an

eternal despair of knowing either their principle of their

purpose? All things emerge from nothing and are borne onwards to

infinity. Who can follow this marvelous process? The Author of

these wonders understands them. None but he can. |

4.

Cogito Ergo Sum

4.1 The

First Item of Knowledge

Famously, Descartes puts forward a very simple candidate as the “first item

of knowledge.” The candidate is suggested by methodic doubt—by the very

effort at thinking all my thoughts might be mistaken. Early in the Second

Meditation, Descartes has his meditator observe:

I have

convinced myself that there is absolutely nothing in the world, no sky, no

earth, no minds, no bodies. Does it now follow that I too do not exist? No:

if I convinced myself of something then I certainly existed. But there is a

deceiver of supreme power and cunning who is deliberately and constantly

deceiving me. In that case I too undoubtedly exist, if he is deceiving me;

and let him deceive me as much as he can, he will never bring it about that

I am nothing so long as I think that I am something. So after considering

everything very thoroughly, I must finally conclude that this proposition, I

am, I exist, is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or

conceived in my mind. (Med. 2, AT 7:25)

As the

canonical formulation has it, I think therefore I am (Latin: cogito ergo

sum; French: je pense, donc je suis)—a formulation which does not expressly

arise in the Meditations.

Descartes regards the ‘cogito’ (as I shall refer to it) as the “first and

most certain of all to occur to anyone who philosophizes in an orderly way”

(Prin. 1:7, AT 8a:7). Testing the cogito with methodic doubt is supposed to

help me appreciate its certainty. For the existence of my body is subject to

doubts that the existence of my thinking resist. Indeed, the very attempt at

thinking away my thinking is self-stultifying.

The

cogito raises numerous philosophical questions and has generated an enormous

literature. In summary fashion, I'll try to clarify a few central points.

First,

a first-person formulation is essential to the certainty of the cogito.

Third-person claims, such as “Icarus thinks,” or “Descartes thinks,” are not

unshakably certain—not for me, at any rate; only the occurrence of my

thought has a chance of resisting hyperbolic doubt. There are a number of

passages in which Descartes refers to a third-person version of the cogito.

But none of these occurs in the context of trying to establish categorically

the existence of a particular thinker (as opposed merely to the conditional

existence of whatever thinks).

Second,

a present tense formulation is essential to the certainty of the cogito.

It's no good to reason that “I existed since I recall I was thinking,”

because methodic doubt calls into question whether I'm having veridical

memories. (Maybe I'm merely dreaming that I was thinking, or maybe an evil

genius is feeding me false memories.) Nor does it work to reason that “I

shall continue to exist since I am now thinking.” As the meditator remarks,

“it could be that were I totally to cease from thinking, I should totally

cease to exist” (Med. 2, AT 7:27). The privileged certainty of the cogito is

grounded in the “manifest contradiction” (cf. AT 7:36) of thinking away my

occurrent thinking.

Third,

the certainty of the cogito depends on being formulated in terms of my

cogitatio—i.e., my thinking, or awareness/consciousness more generally. Any

mode of my thinking is sufficient: doubt, understanding, affirmation,

denial, volition, imagination, sensation, or the like (cf. Med. 2, AT 7:28).

My non-thinking activities, on the other hand, are insufficient. For

instance, it's no good to reason that “I exist since I am walking,” because

methodic doubt calls into question the existence of my legs. (Maybe I'm just

dreaming that I have legs.) A simple revision, such as “I exist since it

seems I'm walking,” restores the anti-sceptical potency (cf. Replies 5, AT

7:352; Prin. 1:9).

A

caveat is in order. That Descartes rejects the certainty of formulations

presupposing the existence of a body commits him to nothing more than an

epistemological distinction between mind and body, but not yet an

ontological distinction (as in substance dualism). Indeed, in the passage

following the cogito, Descartes has his meditator say:

And yet

may it not perhaps be the case that these very things which I am supposing

to be nothing [e.g., “that structure of limbs which is called a human

body”], because they are unknown to me, are in reality identical with the

“I” of which I am aware? I do not know, and for the moment I shall not argue

the point, since I can make judgements only about things which are known to

me. (Med. 2, AT 7:27)

Fourth,

and related to the foregoing quotation, is that Descartes' reference to an

“I”, in the “I think”, is not intended to presuppose the existence of a

substantial self. Indeed, in the very next sentence following the initial

statement of the cogito, the meditator says: “But I do not yet have a

sufficient understanding of what this ‘I’ is, that now necessarily exists”

(Med. 2, AT 7:25). The cogito purports to yield certainty that I exist

insofar as I am a thinking thing, whatever that turns out to be. The ensuing

discussion is intended to help arrive at an understanding of the ontological

nature of the thinking subject.

More

generally, one should keep distinct issues of epistemic and ontological

dependence. In the final analysis, Descartes thinks he shows that the

occurrence of my thought depends (ontologically) on the existence of a

substantial self—to wit, on the existence of an infinite substance, namely

God (cf. Med. 3, AT 7:48ff). But Descartes denies that an acceptance of

these ontological matters is epistemically prior to the cogito: its

privileged certainty is not supposed to depend (epistemically) on abstruse

metaphysics.

Granting that the cogito does not presuppose a substantial self, what then

is the epistemic basis for injecting the “I” into the “I think”? Many

critics have complained that, in referring to the “I”, Descartes begs the

question—that he presupposes what is supposedly established in the “I

exist.” Among the critics, Bertrand Russell objects that “the word ‘I’ is

really illegitimate”; that Descartes should have, instead, stated “his

ultimate premiss in the form ‘there are thoughts’.” Russell adds that “the

word ‘I’ is grammatically convenient, but does not describe a datum.” (1945,

567) Accordingly, “there is pain” and “I am in pain” have different

contents, and Descartes is entitled only to the former.

One

effort at reply has it that introspection reveals more than what Russell

allows—it reveals the subjective character of experience. On this view,

there is more to the phenomenal story of being in pain than is expressed by

saying that there is pain: in the former case, there is pain plus a

point-of-view—a phenomenal surplus that's difficult to characterize except

by adding that “I” am in pain, that the pain is mine. Importantly, my

awareness of this subjective feature of experience does not depend on an

awareness of the metaphysical nature of a thinking subject. If we take

Descartes to be using ‘I’ to signify this subjective character, then he is

not smuggling in something that's not already there: the “I”-ness of

consciousness turns out to be (contra Russell) a primary datum of

experience. And though, as Hume persuasively argues, introspection reveals

no sense impressions suited to the role of a thinking subject, Descartes,

unlike Hume, feels no pressure to reduce all of our concepts to sense

impressions. Descartes' idea of the self does ultimately draw on innate

conceptual resources.

Fifth,

much of the debate over whether the cogito involves inference, or is instead

a simple intuition (roughly, self-evident), is preempted by three

observations. One observation concerns the absence of an express ‘ergo’

(‘therefore’) in the Second Meditation account. It seems a mistake to

emphasize this absence, as if suggesting that Descartes denies any role for

inference. For the Second Meditation passage is the one place (of his

various published treatments ) where Descartes explicitly details a line of

inferential reflection leading up to the conclusion that I am, I exist. His

other treatments merely say the ‘therefore'; the Meditations treatment

unpacks it. A second observation is that it seems a mistake to assume that

the cogito must either involve inference, or intuition, but not both. There

is no inconsistency in the view that the meditator comes to appreciate the

persuasive force of the cogito by means of inferential reflection, while

also holding that his eventual conviction is not grounded in inference. A

third observation is that what one intuits might well include an inference:

it is widely held among philosophers today that modus ponens is

self-evident, and yet it contains an inference. There is no inconsistency in

claiming a self-evident grasp of a proposition with inferential structure—a

fact applicable to the cogito. As Descartes writes:

When

someone says “I am thinking, therefore I am, or I exist,” he does not deduce

existence from thought by means of a syllogism, but recognizes it as

something self-evident by a simple intuition of the mind. (Replies 2, AT

7:140)

4.2 But

is it Knowledge?

There

are interpretive disputes about whether the cogito is supposed to count as

indefeasible Knowledge. (That is, about whether it thus counts upon its

initial introduction, prior to the arguments for a non-deceiving God.) Many

commentators hold that it is supposed to count as indefeasible Knowledge.

But the case for this interpretation is by no means clear.

There

is no disputing that Descartes characterizes the cogito as the “first item

of knowledge [cognitione]” (Med. 3, AT 7:35); as the first “piece of

knowledge [cognitio]” (Prin. 1:194, AT 8a:7). Noteworthy, however, is the

Latin terminology (‘cognitio’ and its cognates) that Descartes uses in these

characterizations. As discussed in Section 1.3, Descartes is a contextualist

in the sense that he uses ‘knowledge’ language in two different contexts of

clear and distinct judgments: the less rigorous context includes defeasible

judgments, as in the case of the atheist geometer (who can't block

hyperbolic doubt); the more rigorous context requires indefeasible

judgments, as with the brand of Knowledge sought after in the Meditations.

Worthy

of attention is that Descartes characterizes the cogito using the same

cognitive language that he uses to characterize the atheist's defeasible

cognition. Recall that Descartes writes of the atheist's clear and distinct

grasp of geometry: “I maintain that this awareness [cognitionem] of his is

not true knowledge [scientiam]” (Replies 2, AT 7:141). This alone does not

prove that the cogito is supposed to be defeasible. It does, however, prove

that calling it the “first item of knowledge” doesn't entail that Descartes

intends it as indefeasible Knowledge.

Bearing

further on whether the cogito counts as indefeasible Knowledge—available

even to the atheist—is the No Atheistic Knowledge Thesis (cf. Section 1.3

above). Descartes makes repeated and unequivocal statements implying this

thesis. Consider the following texts, each arising in a context of

clarifying the requirements of indefeasible Knowledge (all italics are

mine):

For if

I do not know this [i.e., whether God is a deceiver], it seems that I can

never be completely certain about anything else. (Med. 3, AT 7:36, trans.

altered)

I see

that the certainty of all other things depends on this [knowledge of God],

so that without it nothing can ever be perfectly known [perfecte sciri].

(Med. 5, AT 7:69)

[I]f I

did not possess knowledge of God … I should thus never have true and certain

knowledge [scientiam] about anything, but only shifting and changeable

opinions. (Med. 5, AT 7:69)

And

upon claiming finally to have achieved indefeasible Knowledge:

Thus I

see plainly that the certainty and truth of all knowledge [scientiae]

depends uniquely on my awareness of the true God, to such an extent that I

was incapable of perfect knowledge [perfecte scire] about anything else

until I became aware of him. (Med. 5, AT 7:71)

These

texts make a powerful case that nothing can be indefeasibly Known prior to

establishing that we're creatures of an all-perfect God, not an evil genius.

These texts make no exceptions. Descartes looks to hold that hyperbolic

doubt is utterly unbounded—that it undermines all manner of judgments.

Other

texts can be cited in support of the interpretation of the cogito as

indefeasible Knowledge. For example, we have seen texts making clear that it

resists hyperbolic doubt. Often overlooked, however, is that it is only

subsequent to the introduction of the cogito that Descartes has his

meditator first notice the manner in which clear and distinct perception is

both resistant and vulnerable to hyperbolic doubt: the extraordinary

certainty of such perception resists hyperbolic doubt while it is occurring;

it is vulnerable to hyperbolic doubt upon redirecting one's perceptual

attention. This theme is developed more fully in the next Section below.

As will

emerge, there are two main kinds of interpretive camps concerning how to

deal with the Cartesian Circle. The one camp contends that hyperbolic doubt

is utterly unbounded. On this view, the No Atheist Knowledge Thesis is taken

quite literally. The other camp contends that hyperbolic doubt is bounded;

that is, that the cogito, and a few other special truths, are in a lock box

of sorts, utterly protected from even the most hyperbolic doubt. This view

allows that atheists can have indefeasible Knowledge. These two kinds of

interpretations are developed in Section 6.

Further

reading: For important passages in Descartes' handling of the cogito, see

the second and third sets of Objections and Replies. In the secondary

literature, see Beyssade (1993), Hintikka (1962), and Markie (1992). For

especially innovative interpretations, see Broughton (2002) and Vinci

(1998).

5.

Epistemic Privilege and Defeasibility

The

extraordinary certainty and doubt-resistance of the cogito marks an

Archimedean turning point in the meditator's inquiry. Descartes builds on

its impressiveness to help clarify further epistemic theses. The present

Section considers two such theses about our epistemically privileged

perceptions. First, that clarity and distinctness are, jointly, the mark of

our epistemically best perceptions (notwithstanding that such perception

remains defeasible). Second, that judgments about one's own mind are

epistemically privileged compared with those about bodies.

5.1 Our

Epistemic Best: Clear and Distinct Perception and its Defeasibility

The

opening four paragraphs of the Third Meditation are pivotal. Descartes uses

them to codify the phenomenal marks of our epistemically best perceptions,

while clarifying also that even this impressive epistemic ground falls short

of the goal of indefeasible Knowledge. This sobering realization is what

leads to Descartes' infamous efforts to refute the Evil Genius Doubt, by

proving a non-deceiving God.

The

first and second paragraphs portray the meditator attempting to build on the

success of the cogito by identifying a general principle of certainty: “I am

certain that I am a thinking thing. Do I not therefore also know what is

required for my being certain about anything?” (AT 7:35). What are the

phenomenal marks of this impressive perception—what is it like to have

perception that good? Descartes' descriptive answer: “In this first item of

knowledge there is simply a clear and distinct perception of what I am

asserting” (ibid.).

The

third and fourth paragraphs help clarify (among other things) what Descartes

takes to be epistemically impressive about clear and distinct perception,

though absent from external sense perception. The third paragraph has the

meditator observing:

Yet I

previously accepted as wholly certain and evident many things which I

afterwards realized were doubtful. What were these? The earth, sky, stars,

and everything else that I apprehended with the senses. But what was it

about them that I perceived clearly? Just that the ideas, or thoughts, of

such things appeared before my mind. Yet even now I am not denying that

these ideas occur within me. But there was something else which I used to

assert, and which through habitual belief I thought I perceived clearly,

although I did not in fact do so. This was that there were things outside me

which were the sources of my ideas and which resembled them in all respects.

Here was my mistake; or at any rate, if my judgement was true, it was not

thanks to the strength of my perception. (Med. 3, AT 7:35)

The

very next paragraph (the fourth) draws the contrast, emphasizing the

impressive certainty of clear and distinct perception. As earlier noted

(Section 1.1), the certainty of interest to Descartes is psychological in

character, though not merely psychological. Not only does occurrent clear

and distinct perception resist doubt, it provides a kind of cognitive

illumination. Both of these epistemic virtues—its doubt-resistance, and its

luminance—are noted in the fourth paragraph:

[Regarding] those matters which I think I see utterly clearly with my mind's

eye … when I turn to the things themselves which I think I perceive very

clearly, I am so convinced by them that I spontaneously declare: let whoever

can do so deceive me, he will never bring it about that I am nothing, so

long as I continue to think I am something; or make it true at some future

time that I have never existed, since it is now true that I exist; or bring

it about that two and three added together are more or less than five, or

anything of this kind in which I see a manifest contradiction. (Med. 3, AT

7:36)

The

contrast drawn in the third and fourth paragraphs gets at a theme that

Descartes thinks crucial to his broader project: namely, that there is “a

big difference”—an introspectible difference—between external sense

perception, and perception that is genuinely clear and distinct. The

external senses result in, at best, “a spontaneous impulse” to believe

something, an impulse we're able to resist. In contrast, occurrent clear and

distinct perception is utterly irresistible: “Whatever is revealed to me by

the natural light—for example that from the fact that I am doubting it

follows that I exist, and so on—cannot in any way be open to doubt.” (Med.

3, AT 7:38) As Descartes repeatedly conveys: “my nature is such that so long

as I perceive something very clearly and distinctly I cannot but believe it

to be true” (Med. 5, AT 7:69; cf. 3:64, 7:36, 7:65, 8a:9).

Because

of the epistemic impressiveness of clarity and distinctness (notably, as

exhibited in the cogito), the meditator concludes that it will issue as the

mark of truth, if anything will. He tentatively formulates the following

candidate for a truth criterion: “I now seem [videor] to be able to lay it

down as a general rule that whatever I perceive very clearly and distinctly

is true” (Med. 3, AT 7:35). I shall call this general principle the ‘C&D

Rule’. The announcement of the candidate criterion is carefully tinged with

caution (videor), as the C&D Rule has yet to be subjected to hyperbolic

doubt. Should it turn out that clarity and distinctness—as ground—is

shakable, then, there would remain some doubt about the general veracity of

clear and distinct perception: in that case, the mere fact that a matter was

clearly and distinctly perceived “would not be enough to make me certain of

the truth of the matter” (ibid.). This cautionary note anticipates the

sobering realization of the fourth paragraph, that, for all its

impressiveness, even clear and distinct perception is in some sense

defeasible.

In what

sense defeasible? Recall that the Evil Genius Doubt is, fundamentally, a

doubt about our cognitive natures. Maybe my mind was made flawed, such that

I go wrong even when my perception is clear and distinct. As the meditator

conveys in the fourth paragraph, my creator might have “given me a nature

such that I was deceived even in matters which seemed most evident,” with

the consequence that “I go wrong even in those matters which I think I see

utterly clearly with my mind's eye” (AT 7:36). The result is a kind of

epistemic schizophrenia:

Moments

of epistemic optimism: While I am directly attending to a

proposition—perceiving it clearly and distinctly—I enjoy an irresistible

cognitive luminance and my assent is compelled.

Moments

of epistemic pessimism: When I am no longer directly attending—no longer

perceiving it clearly and distinctly—I can entertain the sceptical

hypothesis that the irresistible cognitive luminance is epistemically

worthless, being simply a trick played on me by an evil genius.

The

doubt is thus indirect, in the sense that these moments of epistemic

pessimism arise when I am no longer directly attending to the propositions

in question. This indirect operation of hyperbolic doubt is conveyed not

only in the fourth paragraph, but in numerous other texts, including the

following:

Admittedly my nature is such that so long as I perceive something very

clearly and distinctly I cannot but believe it to be true. But my nature is

also such that I cannot fix my mental vision continually on the same thing,

so as to keep perceiving it clearly; and often the memory of a previously

made judgement may come back, when I am no longer attending to the arguments

which led me to make it. And so other arguments can now occur to me which

might easily undermine my opinion, if I were unaware of God; and I should

thus never have true and certain knowledge about anything, but only shifting

and changeable opinions. For example, when I consider the nature of a

triangle, it appears most evident to me, steeped as I am in the principles

of geometry, that its three angles are equal to two right angles; and so

long as I attend to the proof, I cannot but believe this to be true. But as

soon as I turn my mind's eye away from the proof, then in spite of still

remembering that I perceived it very clearly, I can easily fall into doubt

about its truth, if I am unaware of God.For I can convince myself that I

have a natural disposition to go wrong from time to time in matters which I

think I perceive as evidently as can be. (Med.5, AT 7:69-70; cf. AT 3:64-65;

AT 8a:9-10).

Granted, this indirect doubt is exceedingly hyperbolic. Even so, it means

that we lack fully indefeasible Knowledge. Descartes thus closes the fourth

paragraph as follows:

And

since I have no cause to think that there is a deceiving God, and I do not

yet even know for sure whether there is a God at all, any reason for doubt

which depends simply on this supposition is a very slight and, so to speak,

metaphysical one. But in order to remove even this slight reason for doubt,

as soon as the opportunity arises I must examine whether there is a God,

and, if there is, whether he can be a deceiver. For if I do not know this,

it seems that I can never be quite certain about anything else. (Med. 3, AT

7:36)

(Note:

The leading role played by the cogito in this four paragraph passage is

easily overlooked. Not only is it the exemplar of judging clearly and

distinctly (paragraph two), it is listed among the propositions (paragraph

four) that are compellingly certain while attended to, though undermined

when we no longer thus attend.)

What

next? How are we to make epistemic progress if even our epistemic best is

subject to hyperbolic doubt? This juncture of the Third Meditation (the end

of the fourth paragraph) marks the beginning point of Descartes' notorious

efforts to refute the Evil Genius Doubt. The efforts involve an attempt to

establish that we are the creatures not of an evil genius, but an

all-perfect creator who would not allow us to be deceived about what we

clearly and distinctly perceive. Before turning our attention (in Section

6), to these efforts let's digress somewhat to consider a Cartesian doctrine

that has received much attention in its subsequent history.

5.2 The

Epistemic Privilege of Judgments About the Mind

Descartes holds that judgments about one's own mind are epistemically better

off than judgments about bodies. In our natural, pre-reflective condition,

however, we're apt to confuse the sensory images of bodies with the external

things themselves, a confusion leading us to think our judgments about

bodies are epistemically impressive.The confusion is clearly expressed

(Descartes would say) in G. E. Moore's famous claim to knowledge—“Here is a

hand”—along with his more general defense of common sense:

I

begin, then, with my list of truisms, every one of which (in my own opinion)

I know, with certainty, to be true. … There exists at present a living human

body, which is my body. This body was born at a certain time in the past,

and has existed continuously ever since … But the earth had existed also for

many years before my body was born … (1962, 32-33)

In

contrast, Descartes writes:

[I]f I

judge that the earth exists from the fact that I touch it or see it, this

very fact undoubtedly gives even greater support for the judgement that my

mind exists. For it may perhaps be the case that I judge that I am touching

the earth even though the earth does not exist at all; but it cannot be

that, when I make this judgement, my mind which is making the judgement does

not exist. (Prin. 1:11, AT 8a:8-9)

Methodical doubt is intended to help us appreciate the folly of the

commonsensical position—helping us to recognize that the perception of our

own minds is “not simply prior to and more certain … but also more evident”

than that of our own bodies (Prin. 1:11, AT 8a:8). “Disagreement on this

point,” writes Descartes, comes from “those who have not done their

philosophizing in an orderly way”; from those who, while properly

acknowledging the “certainty of their own existence,” mistakenly “take

‘themselves’ to mean only their bodies”—failing to “realize that they should

have taken ‘themselves’ in this context to mean their minds alone” (Prin.

1:12, AT 8a:9).

In

epistemological treatments Descartes underwrites the

mind-better-known-than-body doctrine with methodic doubt. Other reasons

motivate him as well. The doctrine is closely allied with his commitment to

a representational theory of sense perception. On his view of sense

perception, our sense organs and nerves serve as literal mediating links in

the perceptual chain: they stand between (both spatially and causally)

external things themselves, and the brain events that occasion our

perceptual awareness (cf. Prin. 4:196). In veridical sensation, the

immediate objects of sensory awareness are not states of our sense organs

and nerves—much less are they external things themselves. Rather, the

immediate objects of awareness—whether in veridical sensation, or dreams—are

the mind's ideas. Descartes thinks that the fact of physiological mediation

helps explain delusional ideas:

[I]t is

the soul which sees, and not the eye; and it does not see directly, but only

by means of the brain. That is why madmen and those who are asleep often

see, or think they see, various objects which are nevertheless not before

their eyes: namely, certain vapours disturb their brain and arrange those of

its parts normally engaged in vision exactly as they would be if these

objects were present. (Optics, AT 6:141; cf. Med. 6., AT 7:85ff; Passions

26)

Various

passages of the Meditations lay important groundwork for this theory of

perception. For instance, one of the messages of the wax passage is that

sensory awareness does not reach to external things themselves:

We say

that we see the wax itself, if it is there before us, not that we judge it

to be there from its colour or shape; and this might lead me to conclude

without more ado that knowledge of the wax comes from what the eye sees, and

not from the scrutiny of the mind alone. But then if I look out of the

window and see men crossing the square, as I just happen to have done, I

normally say that I see the men themselves, just as I say that I see the

wax.Yet do I see any more than hats and coats which could conceal

automatons? I judge that they are men. (Med. 2, AT 7:32)

Descartes thinks we're apt to be “tricked by ordinary ways of talking”

(ibid.). In colloquial contexts we don't say it seems there are men outside

the window; we say we see them. But that this is our ordinary way of talking

does not help clarify the metaphysical nature of perception. These ordinary

ways of talking do suggest something about our ordinary ways of judging,

namely that judgments about external things are not the result of complex,

conscious inference, as if: “Well, I appear to be awake, and the window pane

looks clean, and there's plenty of light outside, and so on, and I thus

conclude that I am seeing men outside the window.” But again, from facts

about our ordinary ways of judgment formation it does not follow that we

directly perceive external things themselves. (To suppose otherwise is to

conflate epistemic directness and perceptual directness.) When all is

considered carefully, Descartes thinks we should conclude that our

perception does not, strictly speaking, extend beyond the mind's own ideas.

This is an important basis of the mind-better-known-than-body doctrine. In

the concluding paragraph of the Second Meditation, Descartes writes:

I see

that without any effort I have now finally got back to where I wanted. I now

know that even bodies are not strictly perceived by the senses or the

faculty of imagination but by the intellect alone, and that this perception

derives not from their being touched or seen but from their being

understood; and in view of this I know plainly that I can achieve an easier

and more evident perception of my own mind than of anything else. (Med. 2,

AT 7:34)

It is

generally overlooked that the mind-better-known-than-body doctrine is

intended as a comparative rather than a superlative thesis. For Descartes,

the only superlative perceptual state is that of clarity and distinctness:

only it is correctly characterized as our epistemic best. While holding that

introspective judgments are privileged, Descartes regards them as

nonetheless subject to error. Even introspective perception—e.g., our

awareness of occurrent pains and other sensations—must be rendered clear and

distinct to be counted among our epistemic best. Such matters are clearly

and distinctly perceivable, writes Descartes,

…provided we take great care in our judgements concerning them to include no

more than what is strictly contained in our perception—no more than that of

which we have inner awareness. But this is a very difficult rule to observe,

at least with regard to sensations. (Prin. 1:66, AT 8a:32; cf. Prin. 1:68)

Elsewhere, Descartes writes that we do “frequently make mistakes, even in

our judgements concerning pain” (Prin. 1:67). These mistakes arise because

“people commonly confuse this perception [of pain] with an obscure judgement

they make concerning the nature of something which they think exists in the

painful spot and which they suppose to resemble the sensation of pain”

(Prin.1:46, AT 8a:22). For Descartes, the key to infallibility is not simply

that the mind's attention is on its ideas, but that it renders its ideas

clear and distinct.

But how

could I be mistaken in judging, say, that I seem to see a speckled hen with

two speckles? Some philosophers hold that such judgments are infallible.

Descartes holds, to the contrary, that we can be mistaken—quite simply, by

thinking confusedly. To help appreciate his view, notice that our question

is the same, in kind, as asking whether I might be mistaken in judging that

I seem to see a speckled hen with two hundred forty seven speckles. Of

course I might be confused in that case. (Indeed, it is plausible to hold

that only in confusion could my thought seem like that.) Yet there is no

relevant difference that would explain why the one judgment is infallible

(not merely correct), while the other is fallible. For Descartes, both are

fallible; the relevant consideration distinguishing their susceptibility to

error is that the two-speckled case is so much easier to render clear and

distinct. But though simpler ideas are generally easier to make clear and

distinct, simplicity is not a requirement: “A concept is not any more

distinct because we include less in it; its distinctness simply depends on

our carefully distinguishing what we do include in it from everything else”

(Prin. 1:63, AT 8a:31; cf. Prin. 1:45).

Though

Descartes is quite clear as to the fallibility of introspective judgments,

people widely attribute to him a variety of related doctrines that he

rejects. Compare the doctrines of the infallibility of the mental—roughly,

the doctrine that sincere introspective judgments are always true; the

indubitability of the mental—roughly, that sincere introspective judgments

are indefeasible; and omniscience with respect to the mental—roughly, that

one has Knowledge of every true proposition about one's own present contents

of consciousness. (There is some variation in the way these doctrines are

formulated in the literature.) Consider two key texts often cited by those

who attribute such doctrines to Descartes:

I

certainly seem to see, to hear, and to be warmed. This cannot be false; what

is called “having a sensory perception” is strictly just this, and in this

restricted sense of the term it is simply thinking. (Med. 2, AT 7:29)

Now as

far as ideas are concerned, provided they are considered solely in

themselves and I do not refer them to anything else, they cannot strictly

speaking be false; for whether it is a goat or a chimera that I am

imagining, it is just as true that I imagine the former as the latter. As

for the will and the emotions, here too one need not worry about falsity;

for even if the things which I may desire are wicked or even non-existent,

that does not make it any less true that I desire them. Thus the only

remaining thoughts where I must be on my guard against making a mistake are

judgements. (Med. 3, AT 7:37)

On

close inspection, these texts make no claim about the possibility of

introspective judgment error, because these texts are not about formed

judgments. In these passages Descartes is isolating the components of

judgment. His two-faculty theory of judgment requires an interaction between

the perceptions of the intellect and the will's assent (a theory elaborated

in the Fourth Meditation). A sine qua non of judgment error is that there be

an act of judgment, but acts of judgment require both a perceptual act and a

volitional act. Descartes' claim that mere seemings “cannot strictly

speaking be false” is therefore innocuous: for in isolating the mere

seeming, he isolates the perceptual from the volitional. My merely seeming

to see a speckled hen with two speckles could not, per se, involve judgment

error, because it does not involve judgment.

Further

reading: On discussions of truth criteria in the 16th and 17th centuries,

see Popkin (1979). On Descartes' doctrine of ideas, see Chappell (1986),

Hoffman (1996), Jolley (1990), and Nelson (1997). On the defeasibility of

clear and distinct perception (including the cogito), see Newman and Nelson

(1999). On contemporary treatments of infallibility, indubitability, and

omniscience, see Alston (1989) and Audi (1993).

6.

Cartesian Circle

In